Why Black-and-White Street Photography Matters in Southeast Asia

I’ve always believed that the streets of Southeast Asia, so busy with with scooters, food vendors and a lot of unexpected moments are where the region’s most compelling stories unfold.

In Plaza: Southeast Asian Photography, those stories come alive in arresting black-and-white frames that do more than freeze time; they lay bare the power dynamics pulsing beneath the surface of daily life.

Here’s why, as both an observer and a participant in these cities, I find street photography and especially its monochrome form absolutely essential for understanding ASEAN today.

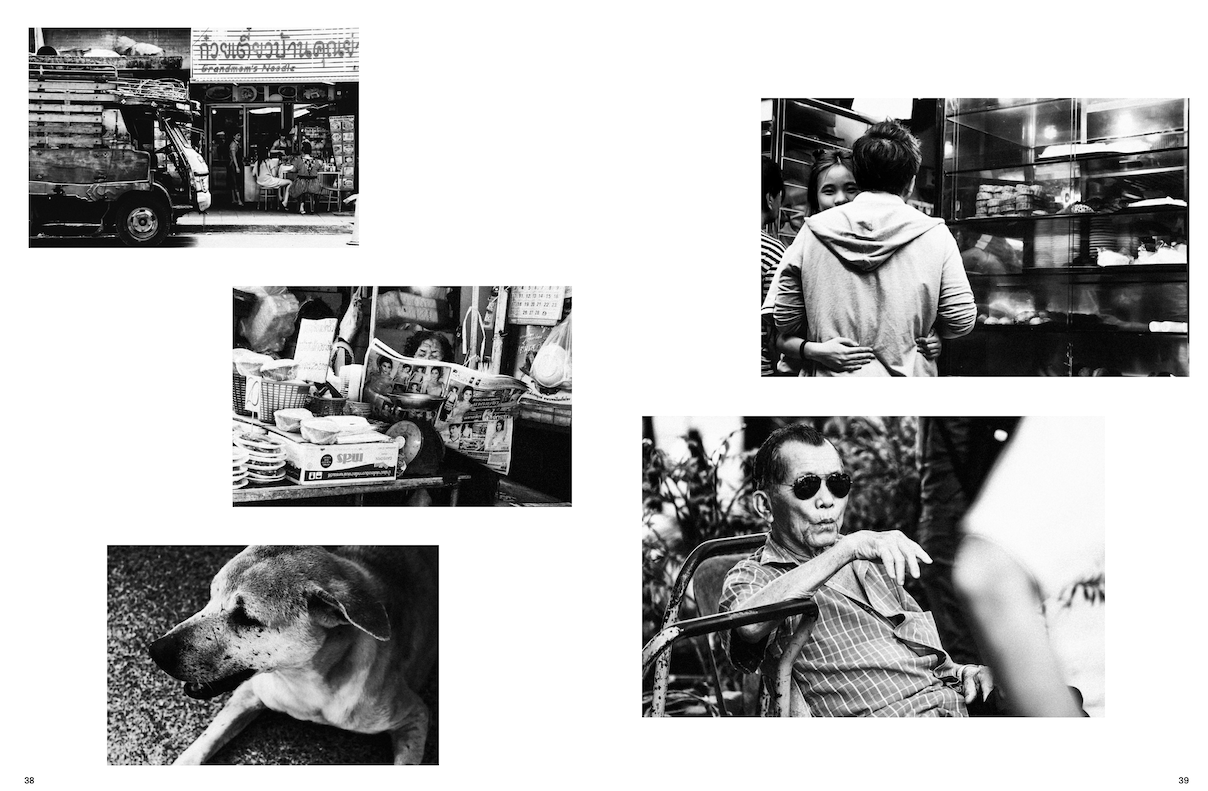

Bangkok montage by Jamie Winder

The Political Concept of ASEAN: Unity in Diversity

Unlike Europe, where borders feel historically settled and journeys from Paris to Prague can be seen through a single cultural lens, ASEAN is often described as a political project as much as a regional identity. It brings together ten nations each with its own language, religion and history under the banner of economic cooperation and diplomatic consensus. Yet, despite this formal framework, the cultural threads weaving through these societies stretch back millennia along the overland and maritime trade routes of the South China Sea.

From the ancient spice markets of Malacca to the Chinese junks docking in Ayutthaya, Southeast Asia has long been at the vanguard of cross-cultural exchange. Indian, Arab, Chinese and later European traders landed on these coasts and left behind zests of cuisine, architectural details and spiritual practices. Today, street photographers document this palimpsest of influences: the kathina procession in Yangon, batik prints in Jakarta, or the lingering colonial facades in Manila’s historic district. In black and white, these frames underscore both the contrasts between ASEAN countries and the connective currents that tie them together.

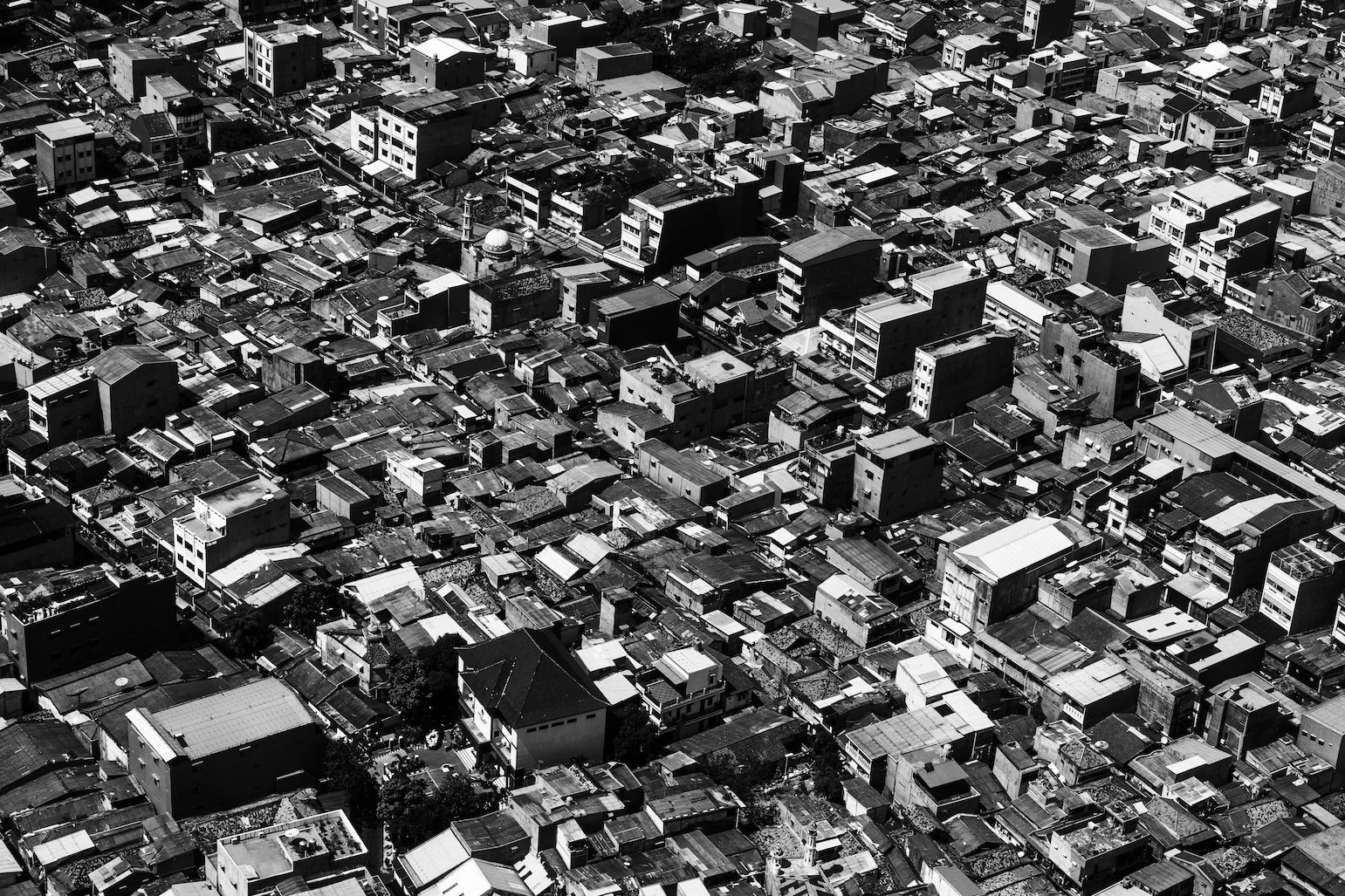

Photograph by Aziziah Diah Aprilya - Makassar, Indonesia

Street Photography as Living Testimony

When you point a camera at a crowded alley in Yangon or at a makeshift market stall in Jakarta, you’re not just taking a picture, you’re staking a claim in the ongoing narrative of that place. Street photography in Southeast Asia doesn’t ask permission; it asserts itself, creating an archive that often slips past official histories. I remember photographing a family of boat-builders on the Mekong Delta, mud-caked feet, weathered hands and a temple spire glimpsed through the haze and feeling that I was capturing the delicate balance between tradition and upheaval.

Photograph by Edmond Leong

Making the Invisible Visible

Rapid urbanization in cities like Ho Chi Minh City or Phnom Penh has given rise to hidden labour forces: motorcycle taxi drivers who ferry people through congested streets, informal recyclers picking through trash for a living, itinerant performers who move from shrine to shrine. Without street photographers documenting these existences, they risk fading into obscurity.

Photograph by Callie Eh

Why Black and White?

Colour photography has its place vibrant festival scenes, the riotous hues of a market stall, but black and white does something different; it distills an image to its emotional core. Without chromatic distraction, shadows sharpen, textures pop, gestures speak louder. Think of the way light fractures through Saigon’s backstreets at dawn, or how the geometry of a Kuala Lumpur shophouse becomes an abstract composition under high-contrast film. In Plaza, these choices aren’t nostalgic; they’re strategic.

Bill Sataya - Jakarta, Indonesia

There’s also a lineage at play. Monochrome links today’s practitioners to Henri Cartier-Bresson’s decisive moments and to the photo essays that shaped our understanding of social documentary in the twentieth century. By echoing that heritage, Southeast Asian street photographers assert a place in the global canon, while also invoking a sense of historical gravitas that colors can sometimes dilute.

Plaza’s Contribution to Regional Dialogue

What makes Plaza so compelling is its cross-border conversation. One spread takes us from Manila’s spray-painted walls to Yangon’s pagoda shadows; the next moves us through Singapore’s gleaming towers to Ho Chi Minh City’s tangled power lines. Yet the black-and-white framework knits these disparate scenes into a cohesive meditation on power. Sidebars and essays delve into topics like environmental precarity and neoliberal development, reminding us that these photographs don’t just hang on gallery walls—they speak to policy, protest and possibility.

Photo by Christian Tâm Schalch - Vietnam

Looking Ahead: Photography as Resistance

Smartphone cameras and social media filters have democratized image-making, but they’ve also accelerated the scroll-and-swipe culture. In that whirlwind, black-and-white street photography stands as a counter-hegemonic act. Its very aesthetic demands slow looking: you linger on that frame of a child wading through Jakarta’s floodwaters, and suddenly you’re drawn into a deeper reflection on climate justice.

Meanwhile, grassroots activists in the region are harnessing photography for accountability, documenting police violence during protests in Bangkok or ecological destruction linked to palm oil plantations in Borneo. In these struggles, monochrome remains a potent tool: it shuns the ephemeral in favor of the enduring, the contemplative over the consumable.

Photograph by Edmond Leong

Conclusion: The Power of the Frame

Street photography in Southeast Asia sits at the intersection of art, anthropology and advocacy. It reminds us that power is not only wielded by governments and corporations, it’s embedded in every shaft of light that cuts across a crowded alley, every face caught at the precise moment of joy, sorrow or determination.

In Plaza: Southeast Asian Photography, black-and-white imagery crystallizes these moments into something more than snapshots: they become calls to witness, to question and, ultimately, to change. And that, to me, is the most powerful photograph of all.

Like what you see? Grab your copy of Plaza here while it’s still available and stay tuned, our second edition is coming soon. Curious about publishing with us? Visit our publishing page.